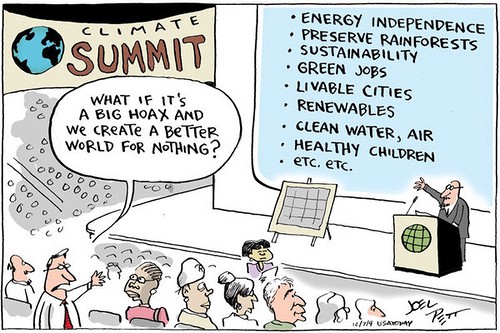

Earlier this year, I read Drawdown, a survey of tools and techniques for addressing climate change ranked by impact. It’s an exceptionally well-researched book and you should read it, but what I want to talk about today is the part of the book that had the most impact on me personally.

The first thing that usually comes to mind when you think about solutions to climate change is renewable energy. But nearly half of the top 20 solutions that Drawdown identifies are related to food, and taken together, changes to the way we produce and eat food account for an impact more than 30% larger than changes to the way we generate electricity.

In particular, Drawdown estimates that the impact of shifting to a diet rich in plants is the 4th-highest-impact of all the 100 solutions they examined, and projects that reducing meat consumption could result in a total reduction in CO₂-equivalent emissions of over 65,000,000,000 tons over the years from 2020–2050. To put that in perspective, that’s comparable to what Drawdown estimates will be the impact of shifting to solar power. It’s six times the estimated impact of shifting to electric vehicles. And it would account for about as much less carbon in the atmosphere as does the ocean, which sequesters about 2.5 Gt/y [1]. The ocean. All of it.

Since I read Drawdown, I’ve been paying much closer attention to the amount of animal products that I eat. I don’t eat zero meat, but I’ve substantially reduced the amount of meat I eat, now at about one meal per week. And I’m wondering if other people are doing the same.

I know that the Baader-Meinhof effect will mean I’m more aware of stores and restaurants offering plant-based options, so it will seem to me subjectively that there’s a growing movement of plant-based food even if there isn’t. Data on vegetarianism and veganism is surprisingly difficult to pin down—studies report anything from 4% to 13% of Americans are vegan or vegetarian[2]—and it’s even harder to find data on people like me who aren’t vegetarian per se, but are choosing to eat less meat. Things get even trickier when you try to correlate those numbers between countries.

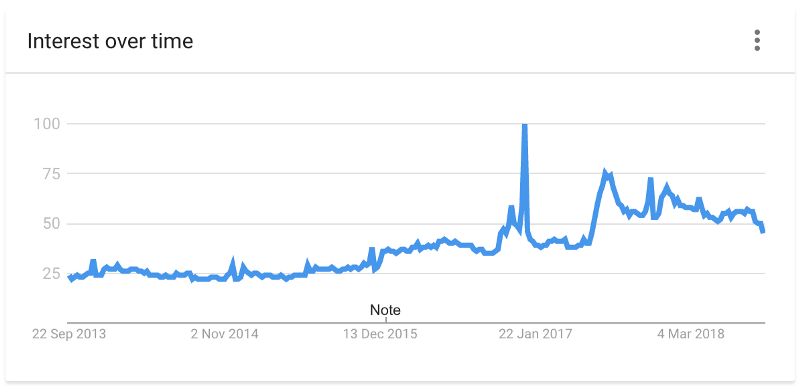

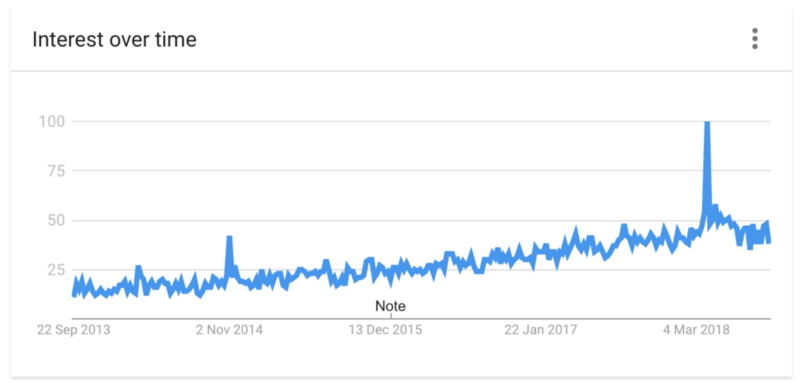

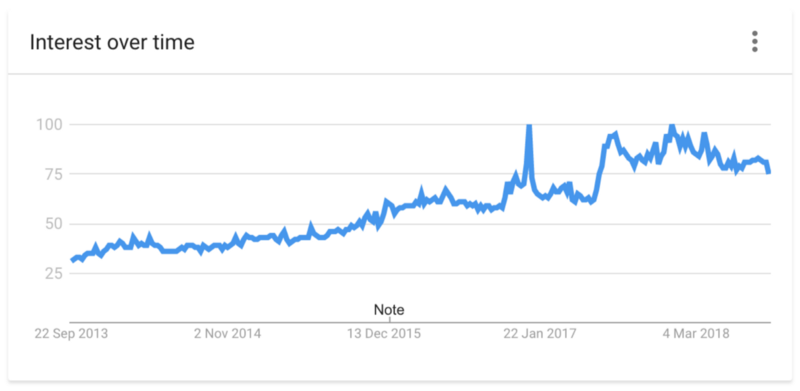

Google Trends is far from an authoritative data source, but perhaps it can be a proxy as part of a broader investigation into whether plant-rich diets are on the rise. I looked at trends for searches for veganism, reasoning that I usually search for those things when I’m eating out in a place I’m unfamiliar with, and that it probably correlates with the number of people who are doing the same sort of thing.

It’s a little difficult to parse this chart, but it looks roughly like veganism is about twice as popular in the U.S. now as it was in 2013. And the trend holds up for other geographies than the U.S., too.

Google Trends only reports data about people who use Google, which notably excludes China (for now) and, largely, India. That’s more than 2 billion people in the world missing from this analysis. China has a rapidly growing middle class who often associate meat with wealth and status. India also has a rapidly growing middle class, but has a large number of adherents to Dharmic religions such as Jainism, Buddhism and Hinduism which prohibit the consumption of meat and as such, India is about 30% vegetarian already.

These graphs would suggest that plant-based diets are on the rise in Western countries, and rapidly so—2x in 5 years is an incredible rate of growth.

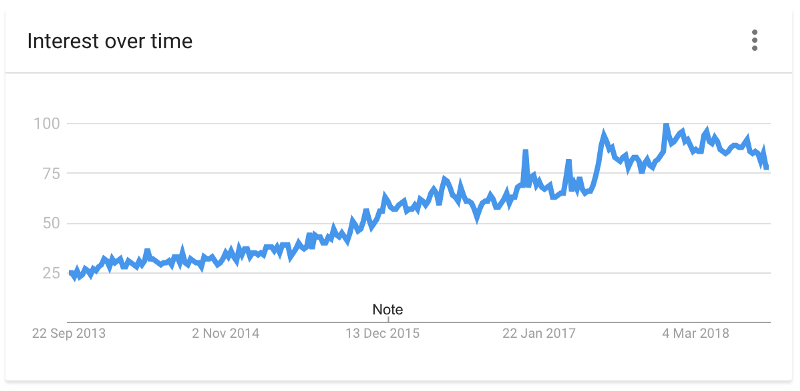

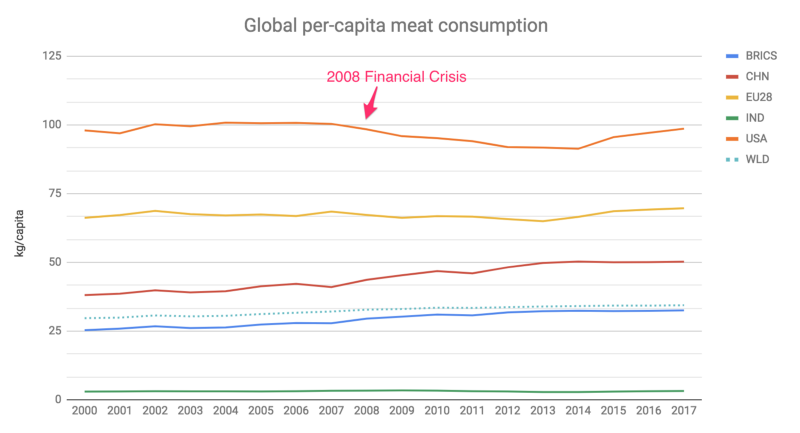

Let’s consult another source of data to see if these trends correlate! I grabbed the OECD’s data on meat consumption, which includes kilograms-per-capita data for 43 countries going back to 1990. The built-in graphing function on the OECD website wouldn’t show me summed meat consumption across types of meat (poultry, beef, etc.) so I downloaded the raw data and plotted it myself. The data for beef didn’t go back before 2000 for some countries, so I’ve plotted just the years 2000–2017.

This chart tells another story. While it looks like people in Europe and the U.S. are eating about the same amount of meat as they always have, people living in Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) are eating nearly 30% more meat than they did 20 years ago (though interestingly, meat consumption in India remains low). Worldwide, per-capita meat consumption is up 15% since 2000.

So it seems that while enthusiasm for plant-based diets is growing in the West (who are by far the hungriest for meat), it isn’t yet an entrant into the cultures of the Global South (which contains vastly more people). Even though the average person in China consumes half as much meat as the average person in the U.S., there are four times as many people living in China.

I don’t know what it will look like for plant-rich diets to take off in China, or Brazil, but it probably won’t look like veganism in the West.

Climate change isn’t a problem that any one of us can have a significant impact on in our personal lives. The scale of the problem is such that effective actions are those at the scale of thousands to millions of people. But eating a plant-rich diet is by far the most impactful change you can make yourself, way way more than recycling or changing your lightbulbs. And you’ll be living your values every time you eat a meal. Assuming you value the continued existence of human life on Earth, that is.

You don’t have to eat 100% vegan—as my wife Cole says, if everyone ate vegan half the time, it’d be like half of us were vegan!—but you do have to start now. We’re running out of time.